Editor’s Note: Washington will be one of the speakers at our Director Resilience 2022 Boardroom Summit Nov. 17-18, an exclusive online retreat for experienced public company directors. Join us >

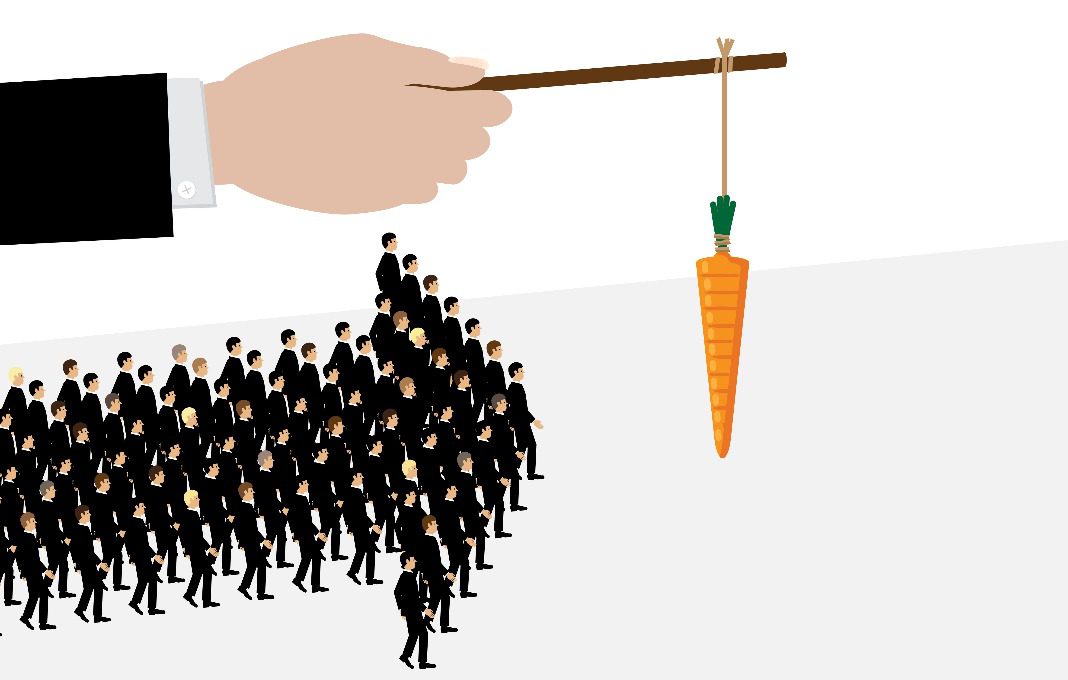

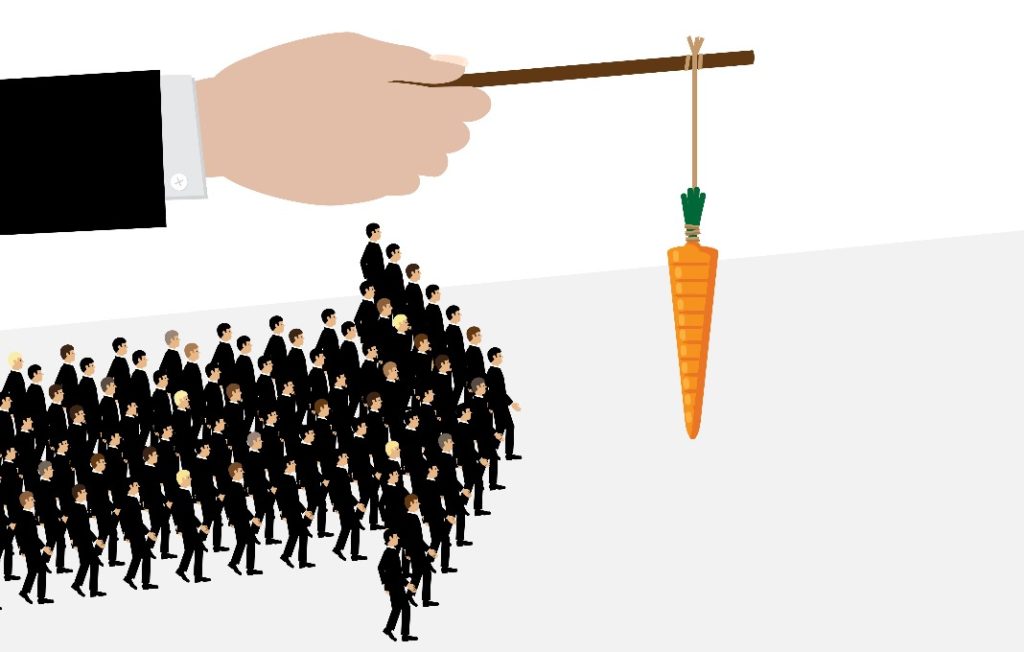

Executive compensation programs have a lot in common with the Internal Revenue Code. The tax code has moved far beyond its essential purpose of raising revenue for the government, or even providing incentives to advance broad-based societal goals such as homeownership. Today it seeks to shape virtually every form of human behavior with a vasty complicated set of rules – and with questionable efficacy.

Executive compensation programs are also used to do much more than provide sufficient compensation to attract, retain, and motivate leaders to successfully execute a firm’s strategy. Often in the name of pay-for-performance, or of greater accountability, they encompass a wide variety of complex mechanisms to shape and reward executive behavior – again, often with questionable efficacy.

While the federal tax code has experienced occasional moments of genuine reform – such as the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (in which I played a minuscule role as a congressional staffer) – executive compensation seems to be on a continuous trajectory toward complexity.

Now many companies are considering linking executive compensation to ESG performance. Indeed, The Conference Board has found that over half the S&P 500 ties CEO compensation to ESG performance. Rather than rushing to add more features to their programs, this could be a moment for board compensation committees to carefully evaluate the costs and benefits of adding ESG metrics and, more broadly, consider the equivalent of tax reform for their executive compensation programs – aiming at (if not necessarily fully achieving) greater simplicity, fairness, and effectiveness.

Unlike the tax code, this is a matter over which corporations have control.

This essay proposes six questions directors should ask before incorporating ESG metrics into their executive compensation programs. It also suggests a deeper re-think of executive compensation.

6 Questions To Ask

First, what are we already doing to achieve our ESG goals? Assuming that there is clear agreement on the company’s ESG goals (if there isn’t, please return to GO), directors should ask management what the firm is already doing to reward the achievement of those goals. This involves existing provisions in the executive compensation programs, as some companies have been factoring employee health and safety, diversity, anti-corruption, and other ESG topics into executive pay for many years. More importantly, compensation committees should not look at the question of rewards in a silo: they should ask what other tools – including instilling sense of accountability via public disclosure – are already being used to keep the company on track.

Second, what are the benefits of doing more to reward achievement of our ESG goals? There may be objectives that could benefit from an additional “push.” But if boards think that one of the benefits of linking executive compensation to ESG metrics is winning points with investors, they may want to think again.

According to one report, most investors want companies to link executive compensation only if they use specific and measurable metrics that are transparently disclosed. But many companies understandably believe that it’s more appropriate to assess performance as part of the “individual performance” section of a bonus plan using qualitative measures. For example, some 90 S&P 500 companies currently consider diversity & inclusion performance as part of the individual performance assessment, versus 33 companies that include it in the business strategy scorecard, and only 16 assess it as a standalone metric.

Third, what are the alternatives to achieving our ESG goals without changing our executive compensation programs? Companies have only so much “real estate” in their executive compensation plans to devote to specific goals. It may be more effective to build ESG factors into succession, promotion, and other forms of internal and external recognition.

Fourth, if we add ESG measures to our executive compensation programs, how should we do it? This raises a whole host of subsidiary questions:

- What topics to cover? For firms in the S&P 500 that link CEO compensation to ESG, it’s most common to tie it to human capital (226 firms), other social issues (143), and governance (87). Just 64 firms tie CEO compensation to environmental performance.

- Whose compensation is affected? Consider whether to cover the CEO, the C-suite, or management and employees generally. Firms often do not involve the entire C-suite. For example, 137 CEOs in the S&P 500 have their compensation tied to diversity and inclusion, but only 84 CFOs do as well. That may change as ESG is integrated more fully into a company’s business and across all of its corporate functions.

- Which plan? It’s most common for companies to consider ESG performance as part of the annual bonus plan rather than a long-term incentive plan: 133 companies in the S&P 500 include diversity & inclusion performance in their annual plan; only 4 do so in their long-term plan. Even environmental goals, which are often inherently long-range, are addressed more often in annual plans (68 firms in the S&P 500) than long-term plans (10).

- What type of objectives, and where to put them? There are two basic types of objectives: qualitative and quantitative, or some combination of the two. And there are generally three ways of incorporating ESG objectives into an incentive plan: as part of an individual’s performance assessment, as part of a “business scorecard,” and as a stand-alone metric. By far the most common practice is to incorporate objectives, usually qualitative in nature, into the individual performance section: 146 firms in the S&P 500 consider ESG as part of their CEO’s individual assessment. By comparison 94 firms do so as part of a business scorecard; and 97 do so as a stand-alone quantitative metric. Most of those stand-alone metrics relate to human capital management and social goals; only 24 CEOs in the S&P 500 have their compensation linked to a stand-alone environmental metric.

And, of course, there are other critical issues to address – such as how much discretion should the compensation committee have in evaluating performance, how reliable are the data used to measure performance, and, at a global company, what are the appropriate measures outside the US?

Fifth, how do we explain these changes to executives and other stakeholders – indeed, how have we engaged them thus far? The best conceived changes to executive compensation programs can often fail at the communication phase. Incorporating ESG measures in executive compensation shouldn’t be a secret project; it’s helpful to solicit input from affected executives and investors before the committee approves changes. It’s also important to consider how the changes will be perceived more broadly. For example, what will be the reaction of employees be if the company links 10% of an executive’s bonus to reduced greenhouse gas emissions, but there is no link to increasing workforce diversity?

Sixth, what next? Committees should ask how management plans to revisit the ESG metrics over time to ensure that they are still aligned and the firm’s strategy and how management intends to assess whether those measures are, in fact, effective.

If compensation committees are comfortable with the answers to these six questions, they can proceed with some confidence. But even so, they may want to pause for a moment and think more broadly about their executive compensation programs.

Keep It Simple

The Covid-19 pandemic and associated economic disruption and social unrest did not, as some expected, lead to a radical overhaul of executive compensation. That is in part because the stock markets generally recovered and so there wasn’t significant investor pressure for major changes in executive compensation.

But the pandemic has caused both firms and individuals to take stock of what they’re doing and why they’re doing it. Having worked with compensation committees for most of the past 30 years, I’m acutely sensitive to the challenges of pressures they’re operating under and the challenge of approving programs that work for management, the board, and investors. Even if it were advisable, I don’t think it’s realistic to wipe the slate clean.

Yet I am suggesting a shift the direction away from ever-increasing complexity. We have seen some shifts in executive compensation in the face of the pandemic, which may prove durable, that point toward greater simplification.[1] We have also seen several instances where compensation committees have stood up to intense shareholder pressure and done what they believed was right for the firm.[2]

So some brave compensation committees may wish to ask themselves, management, and their consultants a few fundamental questions:

- What are we truly trying to accomplish with our executive compensation programs that go beyond retaining and motivating talent?

- Are our programs working? The answer is not given just by looking at a graph that shows how executive compensation moves in the same direction as financial performance and stock performance – which may reflect many factors that go far beyond executive pay. It requires deeper analysis of company and peer data, as well as candid discussions with management.

- What do shareholders and executives really think about our programs in general? Say-on-pay votes are a blunt instrument to convey shareholder views, and even in shareholder engagement companies often ask investors only about the latest changes to executive compensation. Companies may be surprised that some investors do not fully embrace current orthodoxy. For example, performance-based equity may not be as popular as you expect. Committees may also benefit from candid feedback from C-suite executives and others who are involved in developing compensation programs.

- How might we redesign our programs with greater simplicity, fairness, and effectiveness in mind? Executive compensation is often much more complex than pay for even the next level down in the organization; consider whether C-suite executives need so many finely calibrated programs as compared to others; and if they are so attuned to the slightest changes in executive compensation, is that a good thing? In terms of fairness, the discussion should not focus on rough measures such as the CEO/average employee pay ratio. But it can address, within the competitive environment for top talent, whether compensation for the C-suite generally moves in tandem with broader employee compensation. And, perhaps most importantly, committees can discuss the processes they should employ on a periodic basis to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs.

Donna Anderson from T. Rowe Price recently observed on a Conference Board webcast that executive compensation is “trendy.” Not because it’s cool. But because companies and their consultants often rely on peer data to inform the design of their programs, so a practice can become widespread quickly. And these trends do not pass without a trace: instead, they leave an accretion programs and provisions that have led corporate proxy statements to be dominated by the description of executive compensation. Moreover, chasing after the latest trend can whipsaw both executives and investors if programs change too frequently.

Perhaps before companies add ESG measures to their executive compensation programs, they might consider where all of this is leading. Imagine if simplicity, fairness, and effectiveness became a trend in executive compensation. That may do more to advance the cause of ESG than the addition of any specific metric.