CEO turnover rates broke records in 2024, increasing by more than 20 percent among S&P 500 companies, compared to prior year. Halfway through 2025, it doesn’t look a whole lot better. Early indicators point to the benchmark index exceeding that number this year, as CEO tenures continue to shrink on the back of mounting short-term pressures, heightened volatility, cultural shifts and the rapid pace of change.

Corporate Board Member asked nearly 100 board members at some of the largest public companies in the U.S. ($1 billion-plus in annual revenue) about that rising risk, as part of a succession planning survey conducted for the third consecutive year with executive compensation, performance and governance consultancy Farient Advisors. The response was a surprisingly unflinching confidence.

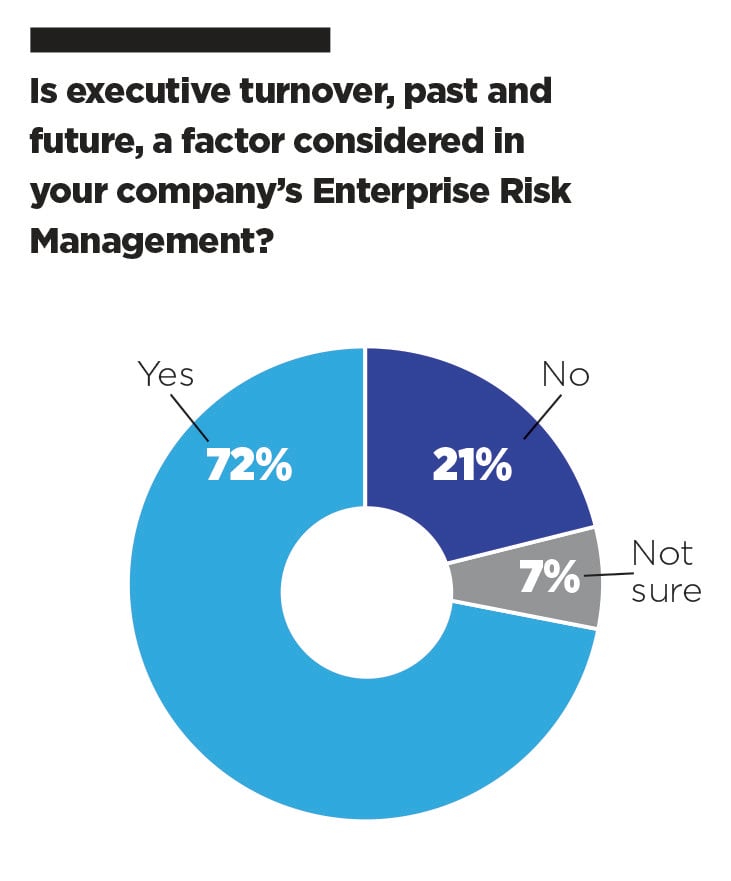

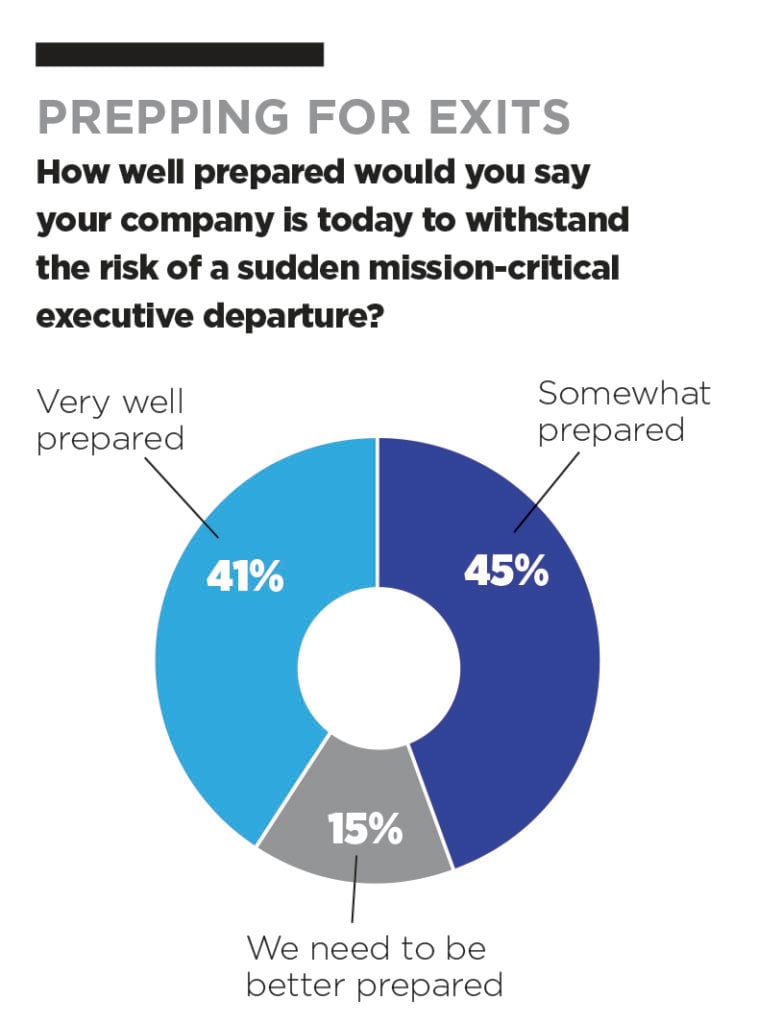

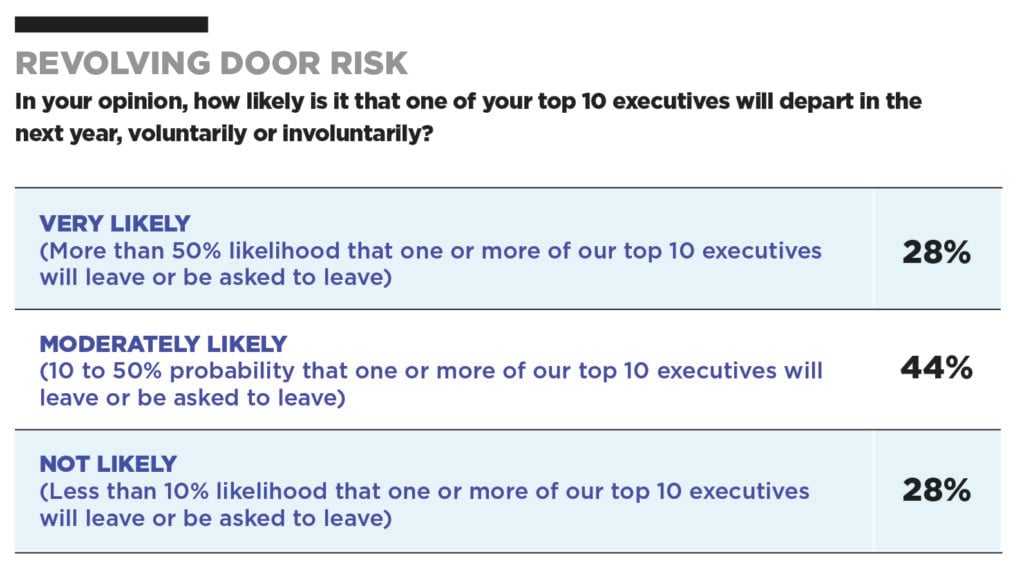

On one hand, directors acknowledge the trend: Half of those polled say they have served on a board where the CEO or a mission-critical executive has departed suddenly and unexpectedly, and 60 percent report having had such a departure just in the past two years. Yet, nearly three-quarters (72 percent) believe it’s unlikely that this will happen again over the next two years, rating that probability as a 50 percent chance or less. And when asked about their preparedness should this nevertheless occur, 86 percent said they’re confident they’re well prepared to sustain the hit without damage to performance or operations.

Gaby Sulzberger, who serves on the boards of MasterCard and Eli Lilly and chaired the Whole Foods board from 2002 through its acquisition by Amazon in 2017, says the high level of confidence in that response is a direct indication that boards are paying attention and taking this risk seriously. “We go through a very rigorous process, with in-depth review of not only CEO succession but also key people, whether or not they are C-Suite or direct reports,” she says. “There’s a formal process and an informal process where we will talk with the CEO about his senior team and where he’s seeing risks and where he has concerns and how he’s thinking about that. It’s hard to think of a topic that’s more important.”

But even boards with robust succession planning processes can struggle to manage a smooth transition after an unplanned exit, notes Marcia Avedon, who serves on the board of publicly traded Acuity, Cornerstone Building Brands and Generac Holdings and is a veteran succession planning expert with decades serving as an HR executive for leading companies such as Trane Technologies, Ingersoll Rand, Merck and Honeywell. “There’s a lot of planned and unplanned turnover right now in the C-Suite, and I think there will be several more years where this will be the case,” she says. “Companies do the process now; they have a succession plan, and they even have emergency names on a piece of paper. But I can tell you from my own board experience, having been on boards for 20 years, the reality versus what’s on that piece of paper don’t always line up.”

Plus, she says, boards can’t lose sight of the risk of an external event forcing an unexpected pivot. “When boards are satisfied with the CEO, there’s not the same sense of risk concern as there should be in many cases,” she said. “But whoever thought in 2020 we would have a global pandemic? Those kinds of existential risks, something horrible happening, people just don’t really think it’s going to happen.”

STRENGTHENING SUCCESSION

Directors agree that an annual review of the succession plan is a common best practice among boards. Boards can further strengthen their plan by stress-testing it against any potential pivot in the strategic direction as well as discerning trends in the market and overall talent landscape, says Jennifer Tejada, who is CEO and chair of NYSE-traded PagerDuty and serves as nom/gov chair on the board of The Estée Lauder Companies. “How is your market changing? What’s the velocity of that change? And therefore, how do you need to plan for leadership, not just the CEO but the complement to the CEO?” she said.

That includes AI. The rapid pace of adoption of AI is changing the way companies are approaching bench-building and succession planning. “If you have a CEO without a technical background in a leadership role in any important branded business, you better have a very strong technical leader alongside of them,” says Tejada. “When you’re, for instance, in a business that is really trying to transition and leverage the benefits of AI and may need to make skillset changes, you may need to bring in somebody who has less commercial experience but more research experience or doesn’t fit the mold of the traditional readynow corporate executive.”

Staggering successors based on their development stages can also help boards avoid a lot of headaches in the event of an emergency succession event, Avedon says. “I’ve seen a wide array where there’s lots of long-term candidates for C-Suite positions, but there’s nobody close. That’s not a good situation to be in because inevitably something’s going to happen, and we don’t have a lot of ready-now talent. And if you’re always going outside, that says something’s wrong in the culture.”

Ideally, boards should identify potential ready-now successors, even if they are not the top candidates for the long term. “What if someone’s being developed, they’re on the list for one to two years and unexpectedly the role comes open?” Avedon asks. “Boards have to get close enough to the development of those successors to say, ‘Are they ready enough?’ That conversation when the talent review discussions happen at the board, you have to ask, ‘If that were to happen, would we put him or her in?’ That’s an important question.”

At any given time, Tejada has two to three leaders on her team who understand the business well enough, understand the financials and have exposure to all stakeholder groups, including the board, to step in should something happen. She says for many boards, that may mean having the board chair step in as interim CEO, but she cautions against relying on those with busy schedules. “I often see these emergency succession plans, but all the emergency backups have day jobs. How’s that going to work? Are they just going to quit their current gig?”

Beyond a departure or unforeseen accident, boards also need to be able to take action rapidly should the market call for an abrupt change at the top. This means having a nom/gov chair who is not afraid to make a change if a change is necessary. “Boards hate changing CEOs,” says Tejada. “It’s high risk, so you need to make sure that that person who’s in the nom/gov role is a person who is steely enough that if a change is needed, whether it’s a reactionary change or a proactive change, that they’re going to lead the committee, partner with the chair or the CEO, whoever is going to drive that activity and make sure that the board executes its fiduciary responsibility in a decisive and timely way. It’s not an easy set of responsibilities, and I wouldn’t put someone in the nom/ gov role who hasn’t led a lot of leadership transition themselves as an operator.”

MITIGATING THE RISK

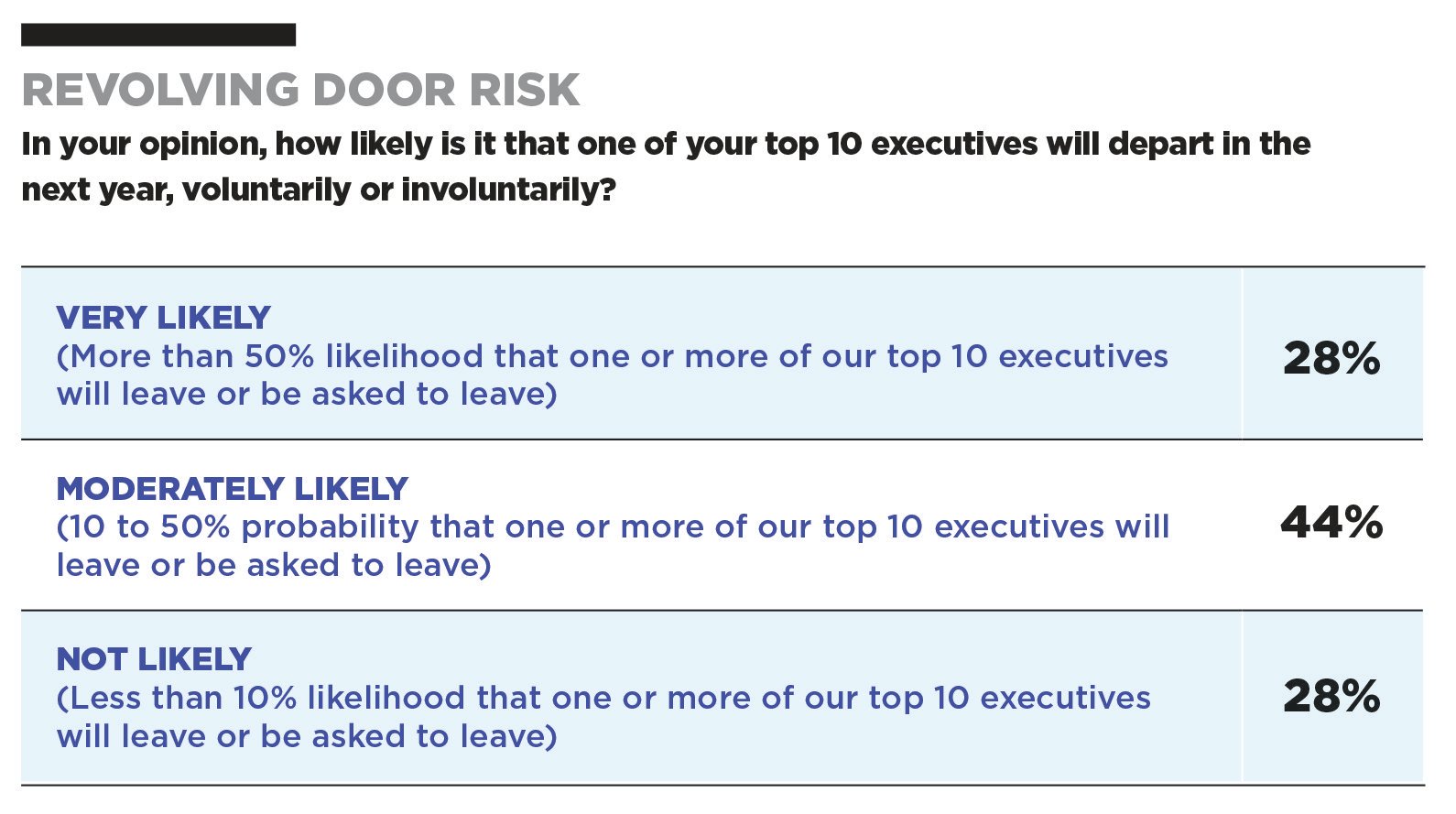

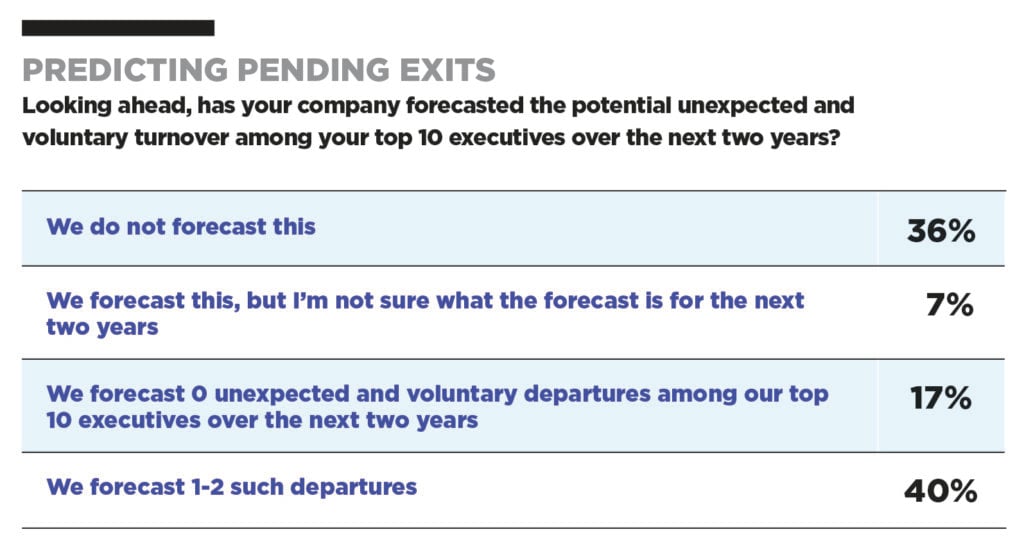

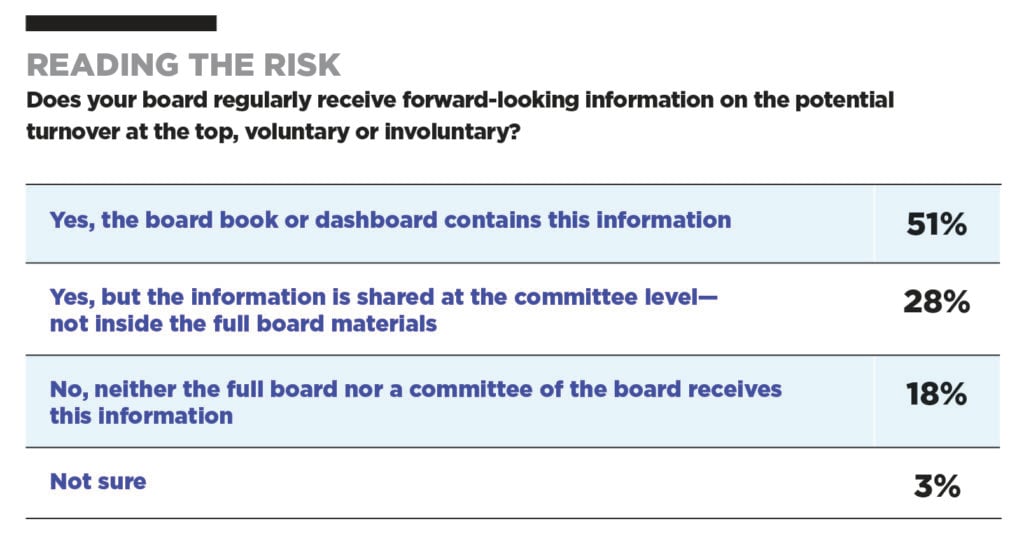

It’s always preferable to work on mitigating the risk rather than responding to it in a crisis. At a minimum, directors agree, an annual review of the succession plan is essential. While that typically entails revisiting the list of candidate successors and assessing their progress—and continued fit—to the role for which they’ve been tapped, directors are divided about the value of forecasting the risk a few years down the road. According to the survey, 36 percent say their company doesn’t forecast the risk of executive turnover at all, and an additional 7 percent say that while they do, they don’t know what that forecast is. That means 43 percent of board members are overseeing succession without clear data on the actual risk of losing these key individuals.

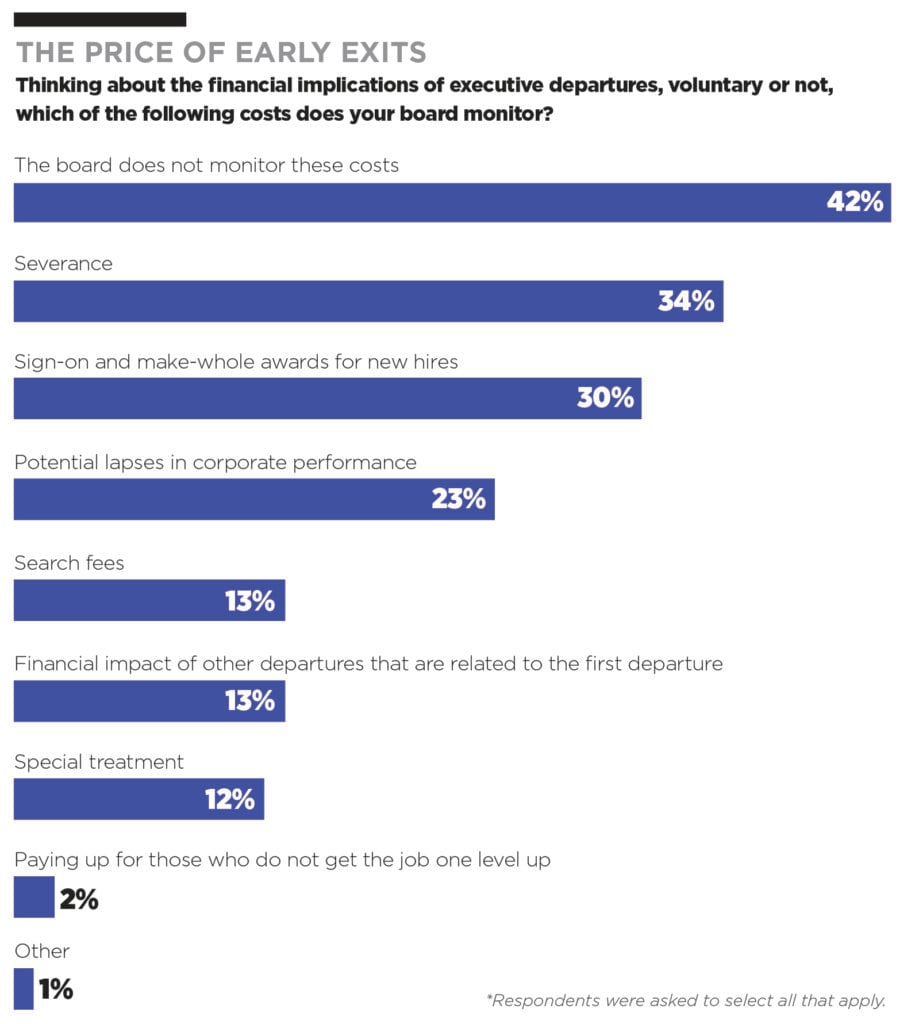

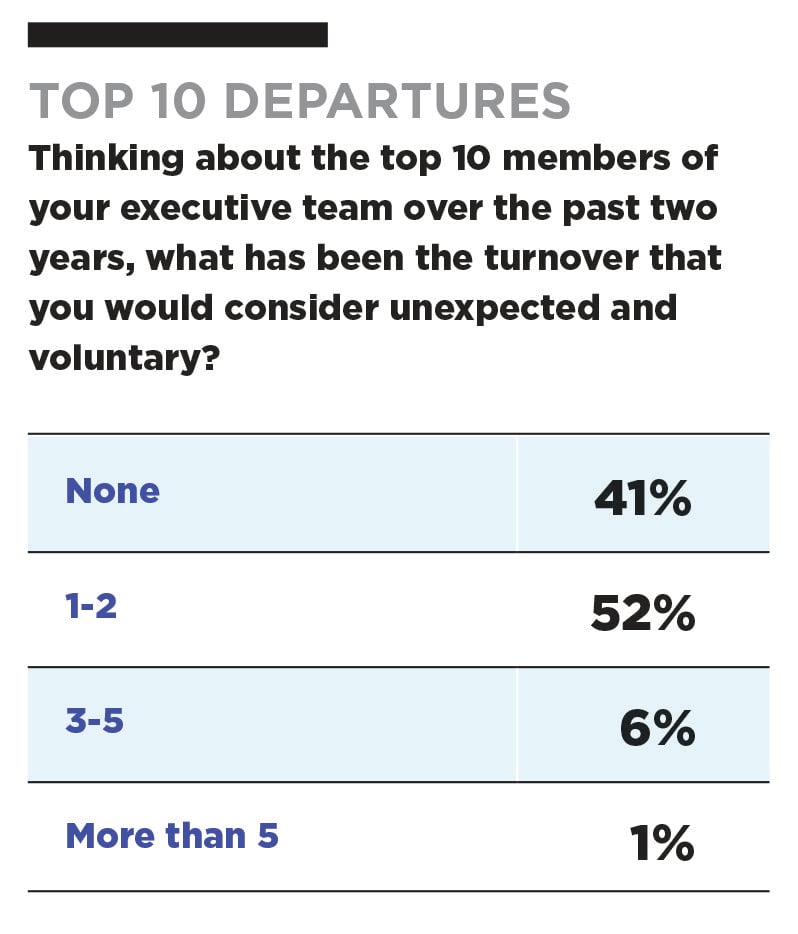

That lack of clarity about CEO turnover risk can be costly, notes Robin Ferracone, founder and CEO of Farient Advisors and chair of the compensation committee at The Woodlands Financial Group. The sudden departure of a leader can cause collateral damage inside the company—what Ferracone describes as a “ripple effect.” “Sudden departures can lead to waves of collateral impact, such as the departure of other C-Suite executives, creating instability beyond the initial vacancy,” Ferracone explains. “This ripple effect also extends to succession candidates, especially when internal candidates are passed over for external hires.”

Companies caught off-guard by a sudden vacancy often look to external candidates when internal candidates aren’t deemed ready to step up. But in general, recruiting externally is far more costly than promoting internally because outside hires are likelier to receive one-time sign-on awards as an inducement or to make the executive “whole” when leaving behind unvested equity.

“Our research shows that externally hired CEOs are paid approximately 30 percent more on average than the outgoing CEOs,” says Ferracone. “By comparison, internally promoted CEOs are typically paid some 20 percent less than the outgoing CEOs.”

Ultimately, those costs also need to be weighed against the company’s strategic goals and expectations for performance, as well as other significant costs such as the loss of institutional knowledge, the disruption of strategic initiatives and a host of other expenses associated with recruiting and onboarding new leadership, says Ferracone, whose firm regularly analyzes the costs and consequences of leadership transitions in all its forms.

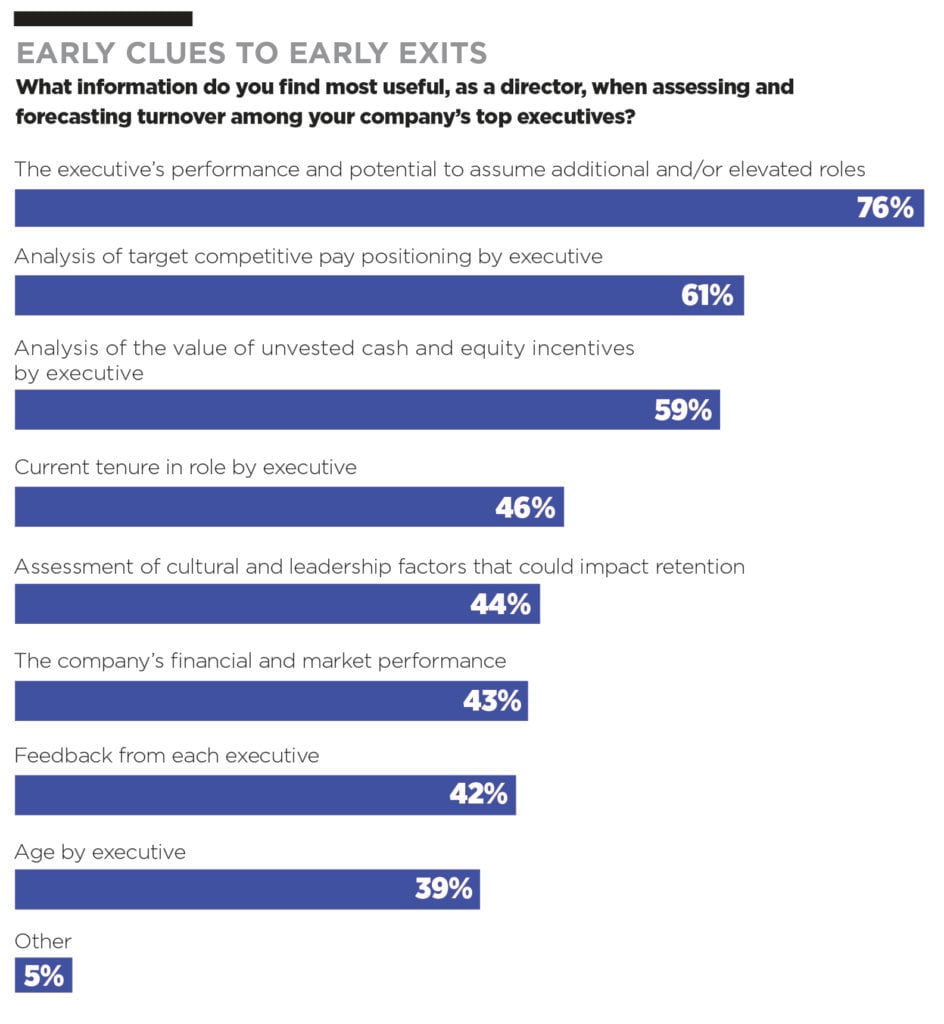

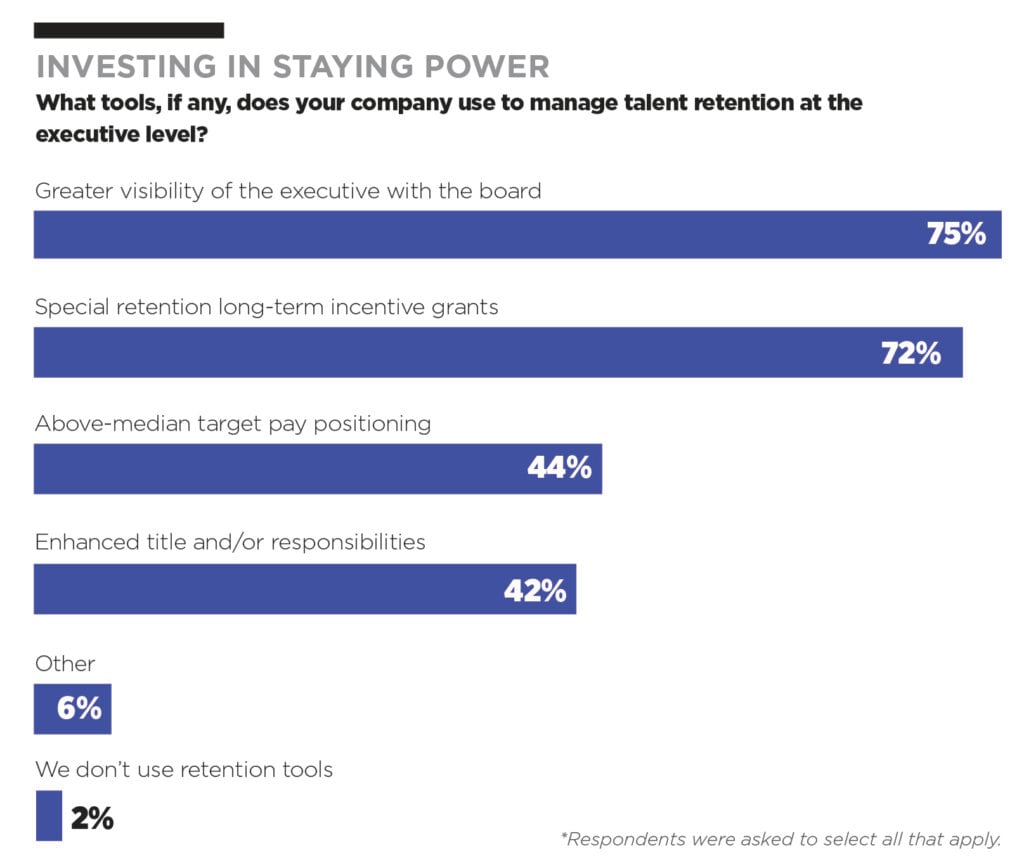

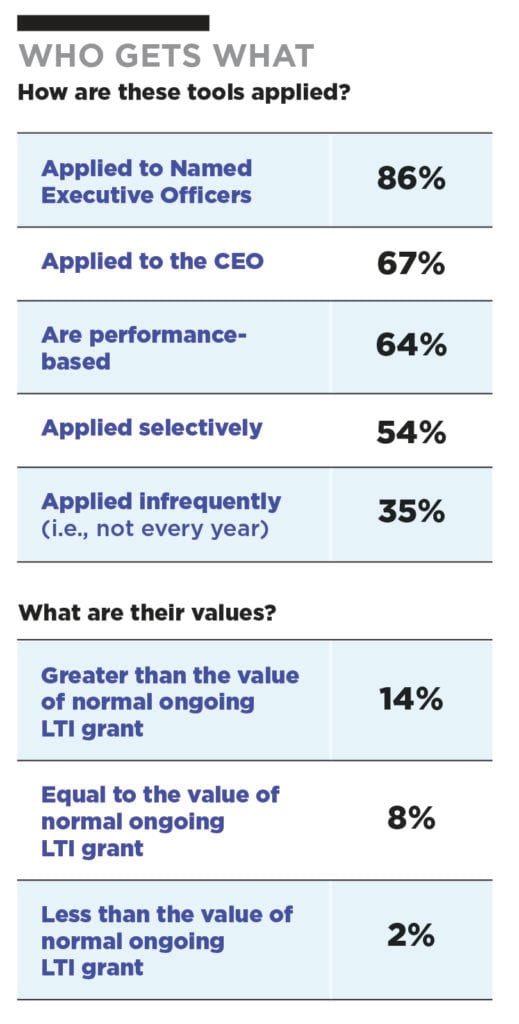

Among directors who say they use turnover projections as part of their succession planning process, the most common metrics used to identify “flight risks” before they leave include the executive’s performance, their compensation relative to peers and the value of their long-term incentive plan. This focus on financial metrics perhaps helps explain why 72 percent say they use “special retention long-term incentive grants” as a tool in their retention strategy for key executives—the second most-used incentive after exposure to the board.

The right pay package is the first line of defense for boards, agrees Avedon. “I’m a believer that the people who are the most critical for the future should not be paid at market. If they’re that important, you should be paying them above market, particularly on the short-term and long-term incentives. Because compensation can communicate a message, motivate and retain talent.”

While 44 percent of directors surveyed agree that above-median pay positioning is a valuable tool for retaining top performers, the results suggest other factors are significant drivers of retention for executives in today’s marketplace. “Of course, money matters,” Tejada says. “They want to be rewarded. They often have a wealth creation goal for their family. They have short-term and long-term financial goals that they want to hit.”

However, the overall culture, mission and purpose of the business also plays an important role, she adds. “Are you bonded with your team, your peers, the executive team and the organization?” she says. “I ask every leader I interview, what do you want to be when you grow up? And it’s really interesting to see how they answer that question. Understanding motivations, goals and interests helps me understand the type of runway and opportunities there may be with each individual.”

One of the most important things boards can do when faced with the risk of losing a critical executive is to have a conversation, agrees Sulzberger. “These are key roles and if you think this person is a flight risk, it warrants a thoughtful conversation about all the reasons why… My bias is very much really understanding each individual situation. Having a clear understanding about what’s going on with regards to key people is an important part of our job,” she said.

But at the end of the day, no board should be aiming for a CEO who never leaves. “My goal is not to keep somebody forever,” Tejada says. “My goal is to have the right leaders in the right moments for the right missions. And that mindset has enabled me to both identify great leaders for what I think we’re going to need in the next two to three years but also let go of leaders who may be more purpose suited for something different somewhere else… Not every leader is going to be equipped for every chapter that you have in your organization.”