As discussed in part I of this series, A Board’s Guide to ESG and Incentives: Effectively Identifying Top ESG Priorities, before an organization can link executive compensation to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals, it must identify material ESG risks and opportunities and establish board oversight in these areas. In part II of the series, A Board’s Guide to ESG and Incentives: Focusing the Company Around ESG Priorities, we covered the subsequent steps of ESG goal-setting, implementation planning, and communication with both internal and external audiences. Now, we turn to the final stage of this journey: incentivizing ESG performance through executive compensation mechanisms.

Once a company has prioritized material ESG issues and communicated meaningful goals, boards and management teams can explore executive compensation linkages to ESG performance. This consideration may be internally motivated to drive accountability towards key strategic outcomes – and/or it could be externally motivated in response to pressure from investors or other stakeholders. While continued investor momentum toward impact and sustainable investing may add pressure on companies to include ESG in incentive plans, it is important for companies to conduct shareholder outreach to understand investor expectations as they can vary. For instance, the 700 global investor signatories to Climate Action 100+ look for disclosure as part of their Net Zero Company Benchmark assessment and whether “the company’s executive remuneration scheme incorporates climate change performance elements.” Alliance Bernstein, on the other hand, expects that all companies should include at least one objectively measurable ESG metric in the incentive plan.

Even though external pressure for ESG pay linkages are rising for many important reasons, corporate boards need to be thoughtful about compensation objectives and design, and whether or when ESG metrics in incentives are right for their company’s circumstances.

Is an ESG incentive right for your company?

As a first step, boards should consider putting ESG metrics into pay when the metrics are important drivers of strategy. From there, boards need to be clear on why they are considering tying ESG metrics into pay. For example, is it to increase the emphasis and drive accountability, respond to external pressure from specific stakeholders, or simply signal importance? Answers to these questions will dictate the most effective incentive design and participant scope. Driving accountability will lead to more specific, carve-out metrics, whereas signaling importance might result in ESG as an individual goal or modifier. For companies looking to achieve multiple objectives, ESG metrics may be strong candidates for inclusion in incentive plans.

Companies should also holistically consider ESG in the context of other strategic priorities and the limited ‘real estate’ in incentive plans—choosing to measure one priority invariably will cause the de-emphasis of another. For example, a company may decide to focus 70% of its annual incentive program (AIP) on traditional financial priorities and 30% on strategic and operational objectives. How that 30% is sub-divided is important. Similar to how companies strive to balance various financial objectives, companies will need to determine the relative emphasis of ESG performance versus other strategic and operational focus areas and decide how much of that 30% to focus on ESG versus innovation, productivity, or other considerations.

If the board decides to incorporate ESG into the pay program, directors need to be thoughtful about which specific ESG metrics will be most effective and what message they send to participants and outside parties. The following questions can help to narrow in on the metrics that are right for the company:

• Is the metric focused on a critical strategic priority?

• Is the metric reflective of a comprehensive, balanced assessment of performance?

• Is there clarity about what outcomes define success, and do participants have clear line-of-sight into how they impact outcomes?

• Is there an opportunity to improve on the metric?

• Is there willingness to maintain the use of an ESG component for an extended time period, even if the company’s strategy or performance shifts over time?

• Is measurement towards the goal absolute and/or relative?

• Is there a way to incorporate stretch goals?

• Is the company willing to disclose externally how and why missed goals were not achieved?

• Are goals measurable within the incentive plan timeframe?

As with the addition of any metric to an incentive program, when companies cannot affirmatively answer these questions, the likelihood of unintended consequences or misaligned incentives increases. Companies that are unsure about any of the above questions may do better by addressing accountability outside pay programs, as described in the final section of this article. Alternatively, companies could consider tracking a measure through a pilot program for a year or two before formally incorporating it into incentives—as they might with any new area of focus. Over time, responses to the above questions may change, so even if ESG metrics are not appropriate today, boards should plan on revisiting these questions at least annually.

How should ESG performance metrics be structured in your incentive plan?

Despite their long-term nature, most ESG metrics are in the AIP (57% prevalence in the S&P 500 as of March 2021, and we expect this number to rise), with fewer than 5% of S&P 500 companies incorporating them in the long-term incentive plan (LTIP) for a number of reasons. ESG goals often have time horizons of five years or more, making it challenging to fit within the typical three-year LTIP performance period. These longer timeframes may also extend beyond some executives’ tenures. This is especially true with the recent study of the average Fortune 500 CEO tenure of 4.6 years. Companies may also find it helps from a motivational standpoint to break long-term goals into annual milestones, which are better suited in the AIP. Another factor may be scope: to apply these incentives to a broader set of employees, many of whom may not participate in an LTIP, embedding them in the AIP makes sense. Accounting rules also dictate that LTIP goals are objective to ensure favorable accounting, limiting the ability to exercise discretion. More European companies incorporate ESG metrics into the LTIP, but it is still not a majority practice. We expect the discussion to continue, and practices to evolve, on the best placement of ESG incentive metrics.

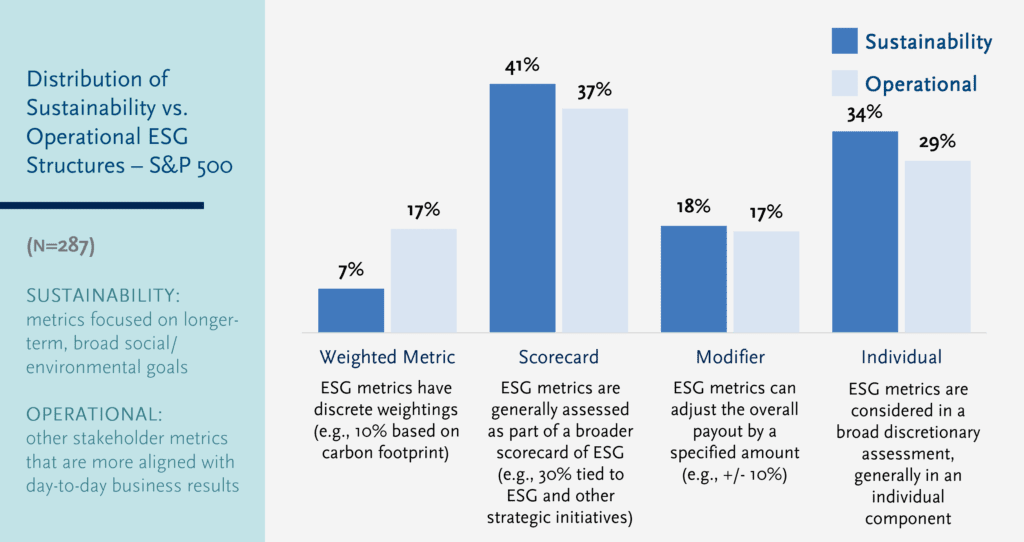

Within the AIP, companies have incorporated ESG metrics in different ways – see figure below for prevalence among S&P 500 companies that have included an ESG metric in their plans. Each approach has benefits and drawbacks.

Source: ESG + Incentives 2021 Report Issue 3. Data as of March 31, 2021.

Sustainability vs. Operational ESG Metrics Various measures of stakeholder interests are often categorized as ESG. We split ESG metrics into two categories: sustainability and operational ESG metrics.

| SUSTAINABILITY ESG METRICS Measures concerned with longer-term, broad social and environmental goals | OPERATIONAL ESG METRICS Other stakeholder metrics that are more aligned with day-to-day business results |

| – Carbon Footprint – Community Engagement – Company Culture – Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion – Emissions/Chemical Containment – Energy Efficiency – Sustainable Sourcing – Waste Reduction – Water Consumption | – Customer Satisfaction – Cybersecurity – Employee Satisfaction – Product Quality – Safety – Talent Development – Turnover/Retention |

Incorporating measures into individual performance assessments may be a good starting point. Still, it can be challenging to move the needle with this approach, particularly if companies do not clearly define specific goals and base the performance assessment on qualitative criteria, which can be subjective. ESG measures in individual assessments are often one of many goals and not shared across executives, diluting their prominence and the shared sense of purpose.

A scorecard approach may be most appropriate for linking pay to multiple strategic and operational priorities, including ESG. For example, a scorecard can assess innovation in products and processes in addition to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) and environmental goals. Alternatively, a company may include improvements in productivity, success in a new channel, and new product sales in a scorecard alongside ESG metrics. The most effective scorecards limit the number of metrics to four or five well-communicated priorities and clearly define goals at the outset of the performance year.

Companies looking to drive meaningful progress against just one or two ESG priorities may choose to assign an explicit weighting for these priorities in the incentive plan. This approach elevates ESG issues but reduces the ability to apply discretion, increasing pressure on the goal-setting process. Incorporating some level of board discretion to override incentive achievements can be important if something unexpected happens, such as a major oil spill or product recalls. As ESG strategies evolve and data becomes more accessible and standardized, boards can refine their approach to AIP integration.

| Approach and Example | When to Use | Advantages | Drawbacks |

| Individual measures (carve-out and modifiers) Example: Comerica has individual metrics for each executive ranging from supplier diversity and sustainability goals to support for diversity, inclusion, and social justice activities | • To signal that ESG progress is important but subordinate to pressing financial and operational goals • When ESG measurements are being developed • To drive individual accountability | • Consumes less real estate in the incentive program • Allows for discretion in assessing impact of individual contributions | • ESG goals and objectives may not be clearly defined, which could be perceived by stakeholders as greenwashing • Impact can get lost within the total incentive program • May lose team focus |

| Scorecards (carve-out and modifiers) Example: CVS Health has a downward workforce diversity modifier based on the Company’s progress in achieving greater diverse leadership representation during the year Example: Coca-Cola will have 10% of its bonus tied to quantitative and qualitative diversity, equity, and inclusion goals in 2022 | • To increase prominence of ESG into the incentive plan balanced with flexibility to establish goals and determine outcomes | • Allows balance with other strategic priorities (e.g., innovation, productivity) • Can mitigate some challenges of setting incentive plan goals for ESG metrics (e.g., GHG emission goals can be difficult to reliably quantify and measure) • Introduces a team-oriented focus to ESG metrics | • With multiple metrics, the impact/importance of any one metric is relatively small • Requires a high level of continued communication to provide clarity |

| Specific, weighted metrics Example: American Water Works has two separate environmental goals (drinking water program compliance and drinking water quality), each with a 7.5% weighting and quantitative goals | • A “burning platform” to make progress on a given ESG measure • When ESG is a fundamental business priority | • Puts ESG metric prominence more on par with traditional financial measures • Makes the goals clear and definitive | • Limited ability to use discretion, which can be a disadvantage where a company is new to setting ESG-related goals and measuring progress • Increases pressure on metric selection and goal-setting given the higher scrutiny placed on selecting a small number of weighted metrics |

What about ESG in long-term incentives?

Many ESG metrics have goals set for 10 years out or more, making it challenging to incorporate within typical LTIPs with a 3-year performance period. Accounting rules dictate that LTIP goals are objective to ensure favorable accounting, limiting the ability to exercise backward-looking judgement which creates another significant hurdle to ESG adoption in the LTIP. Companies may need to think beyond existing one-year bonus and three-year performance share unit (PSU) programs.

Below, we offer a few creative ways ESG might be rewarded in the long-term incentive plan for companies with clear long-term commitments outside of the traditional PSU program. These approaches are currently uncommon, but some outside-the-box thinking can help to mitigate the challenges with “shoehorning” ESG metrics into existing programs.

| Approach | How It Works | Key Considerations |

| Longer-term awards | Lengthen vesting and/or holding periods to 5-7 years, rather than the traditional 3-year period that the majority of LTIPs have in the US (more common in European pay programs) and include an ESG metric with a longer-term goal (e.g., 5 years) | 5-7 years starts to edge into timeframes over which ESG outcomes translate into share price and may align with a company’s longer-term 2025 or 2030 goals, but if granted once (vs. annually with overlapping performance periods), the timeframe may be long for some executive participants who may not be in the role for the full timeframe and for individuals entering or leaving the company during the period |

| Modifier to current time-based equity awards | Add a modifier to restricted stock units (RSUs) of up to 15-20% of the final award. Modifier would apply if performance was significantly above or below a target range of goals (i.e., requires significant outperformance for an upward modifier to be applied). Goals must be objectively measurable to ensure favorable accounting | Separates ESG from the current PSU construct and provides flexibility while companies work on forecasting and setting rigorous, long-term goals. Allows for ESG goals to penetrate deeper into the organization as participation is usually deeper for RSUs than PSUs |

| Separate ESG award | Grant separate ESG awards in cash or equity tied to specific, critical future ESG milestones attached to certain dates (e.g., achieving gender parity in leadership roles by 2030, achieving net zero emissions by 2035, etc.). Awards may pay out above target if the goal is achieved sooner, and below target if the goal takes longer to achieve. Awards would be forfeited if the milestones are not achieved within the specified timeframe (i.e., there should be a date in which the milestone expires) | Reduces the difficulties of setting annual or 3-year targets, which may not fit well with ESG goals. Could overemphasize speed and may not promote goal achievement in a sustainable, cost-effective manner |

How else can companies drive accountability?

In addition to incentive solutions, companies can reinforce accountability on ESG and human capital management (HCM) priorities through strong disclosure, reporting, and performance management. Salesforce publishes quarterly equality updates sharing progress against its hiring and representation goals. General Mills launched 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas (GHG) emission goals and reports annual progress against those goals across its supply chain from packaging to shipping to selling. Promoting individuals and providing development opportunities to those who provide leadership and make strong contributions to a company’s ESG goals or values can send a powerful signal and help move the needle on progress against ESG priorities. Promotions are also compensatory since added responsibilities often come with pay increases. Finally, companies can celebrate success on ESG priorities in other ways aside from compensation through internal and external communications.

—-

A company’s ESG journey requires a tailored strategy—there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to accountability. But for many companies, linking ESG goals with executive compensation incentives can drive accountability internally, increase visibility externally, and support ESG performance across the organization. As we’ve discussed throughout this series of articles, boards need to understand their company’s material ESG risks and opportunities, ensure that management sets meaningful goals and interim milestones, and drive accountability through tailored strategies – which may include executive compensation incentives. Before implementing ESG goals into pay, companies should gain confidence in their measures and know the downstream implications to ensure an effective incentive design and optimize ESG progress. When thoughtfully designed, ESG metrics can create strong reinforcement between a company’s overall strategies and ESG initiatives – and executive pay incentives can create the urgency that drives meaningful change.

Glossary of Key Terms:

- Annual incentive plan (AIP): A plan for compensation that is earned and paid (typically in cash) based upon the achievement of performance goals over a one-year period.

- Long-term incentive plan (LTIP): A plan for compensation that is earned based upon the achievement of performance goals over a longer period of time (often three years). Most commonly in the form of equity vehicles vs. cash.

- Restricted stock units (RSUs): A type of stock-based compensation granted to employees that are subject to a vesting schedule.

- Performance-based restricted stock units (PSUs): Similar to RSUs, a type of stock-based compensation granted to employees but are subject to the achievement of performance goals over a longer period of time (often three years).

- Weighting vs. Modifier: Individual measures and scorecards can either have an explicit weighting (e.g., 20% of the bonus payout) or be structured as a modifier to a bonus payout (e.g., +/- 15% of the bonus payout).

[1] Source: ESG + Incentives 2021 Report Issue 3.